>> Comment: Appointments With Disappointment

>> Comment: Accentuate The Positive?

More...

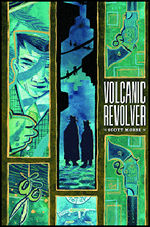

Writer/Artist: Scott Morse

Writer/Artist: Scott Morse

Prologue Lettering: Louis Buhalis

Collecting Volcanic Revolver #1-3 and part of Oni Double Feature #7

Price: $9.95

Publisher: Oni Press

ISBN: 0-9667127-5-7

VOLCANIC REVOLVER is a misunderstanding. Like so much crime fiction, it's built upon stolen knowledge. We don't know who did the deed, who stole the money, who's schtupping the client's wife. But in the case of Scott Morse's thirties crime story, misunderstandings are what the characters cling to.

Vincenzo owns a bakery. He bakes bread and "bread" - he is both an honest food retailer and a mob counterfeiter. Ensconced in the world, he seems as relaxed in its environs as the rest of the cast. Right up until a lonely, confused woman drops off a bomb at his bakery and he is forced to mow her down with the titular firearm. From here, the twisting tale of who the woman was and what it means for Vincenzo and his mob cohorts plays out through the city across three issues.

The New York of Morse's story is an art deco painting of Italy as seen through the eyes of America. Old school idiosyncrasies sit uneasily with the new school direct approach. Vincenzo is, to all intents, endemic of this split, and a representation of history to the younger gangsters. A parental figure, but one they respect as an equal.

Everything from Vicenzo's overt civilian facade as a baker to the titular weapon he brandishes during the Prologue marks him as a fraud, but in Vincenzo's eyes he's more of an embellisher, which is what stops him from ever seeming malevolent. He revels in the storyteller-as-liar dynamic, confiding only in a local child he's training.

The collection unfolds in a regular four-panel-per-page structure, never deviating from this layout. It reads not unlike a strip of celluloid, sliced into more palatable chunks. While the three issues that constitute the original mini are in stark black and white (or a deep brown and white), the bookends are fully painted.

The painted sections are gorgeous, evoking a hazy, midsummer canyon of brick and mortar, light streaking through gaps in the turrets of New York's apartment turrets. Even in a mono-colour printing, the work exudes an atmosphere that is compelling. The brief glimpse of the original colour on the front and back cover shows that a full-colour reprint would have added a further dimension to the work.

The painted sections are gorgeous, evoking a hazy, midsummer canyon of brick and mortar, light streaking through gaps in the turrets of New York's apartment turrets. Even in a mono-colour printing, the work exudes an atmosphere that is compelling. The brief glimpse of the original colour on the front and back cover shows that a full-colour reprint would have added a further dimension to the work.

The line-work that makes up most of the collection is consistently loose. The lines curl and warp over the basic framework of the characters, but never lose their initial configuration. Remaining mostly in close-up, the environs are largely relegated to backgrounds or tracking shots through the city's alleys.

While the large volume of - arguably unnecessary - generic gangsters wandering in and out of Vincenzo's shop are difficult to distinguish, you're never unsure of who the principals are. Indeed, the homogeneity of the criminals pleasantly contrasts with the individuality of the civilians of the piece, such as Freido, the inadvertent double-crosser, and the bad-luck hunchback lady, never able to keep time.

Morse's tale takes its time to get anywhere, leaving this collection with the feeling that an issue is missing. The principal story is fairly simple - a vendetta against Vincenzo is repaid in blood - it's how this story affects the cast that is this collection's real goal. The innocent young boy's brutal conversion to crime, the priest's rendezvous with a lost love.

Vincenzo himself is a wonderful creation: a confessed liar, but a talented artist. Everything he has learnt was learnt in the New World, not in the Old, yet he hangs onto that world's customs. He spends his time converting his young protégé to the Old World dressed as the New. Another example is the mallochio or "evil eye", placed on him by the rival mob. The curse is dispelled by hanging scissors over the door, referenced rather unsubtly when the gangsters pay the curse back by jabbing the aforementioned scissors through a rival mobster's eye.

The lead character seems a touch autobiographical in the way of many of the best small-press creations. He's an artist who also creates stories, who is reticent about revealing where his stories come from. He views his ability to create as equal as his ability to bake bread, but realises it's a devalued skill in this modern era.

It's the priest who feels a stranger to this collection, his story only tangentially connected to the mob vendetta. It's a cute tale about one man and his dog, the only family he has left, and his outsider view of the mob serves to show us how these people interact with civilians. The epilogue's sappy ending seems to suggest a more pleasant interpretation of how criminals behave than reality, but is really just a demonstration of how they look after their own.

It's the priest who feels a stranger to this collection, his story only tangentially connected to the mob vendetta. It's a cute tale about one man and his dog, the only family he has left, and his outsider view of the mob serves to show us how these people interact with civilians. The epilogue's sappy ending seems to suggest a more pleasant interpretation of how criminals behave than reality, but is really just a demonstration of how they look after their own.

With an imminent movie adaptation on the cards, to be directed by Morse himself, it's easy to see how this was heavily influenced by the movies. Morse acknowledges that the story was inspired by watching the flashback sequences in GODFATHER PART II, and the four-panel structure is endemic to the story's heritage. However, the work still retains Morse's unique and ever-changing artistic touch and narrative invention.

With so few period comic works around in any genre, never mind crime, it's often easy to congratulate creators just for trying. But this is more than just a crime tale dressed in antique clothing. The period is the story, religiously researched and effortlessly evoked. The speech is so authentic that a glossary is even reprinted at the back.

VOLCANIC REVOLVER revels in its setting, but doesn't glamorise it. While the characters might not openly acknowledge their foibles, they're there if you read between the lines. Like the titular weapon - the name based on an old man's misunderstanding - a lot of subtext bubbles under the fictional verbiage the characters toss about.

If anything, this book is about the disparity between the rose-tinted visions of the past and the seemingly bloody, emotionally-detached present. In many ways, things are better now, despite what we hear of what's gone before. The truth is that the old ways we hear about are really superstitions and half-truths. Misunderstandings that nobody wants to dig up.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.