It was a small detail that told Carla Speed McNeil she wanted to be an artist. "'I was extremely small, maybe four or five," she remembers, "and I was scribbling away on a piece of paper, and the tone of my mother's voice changed. She was surprised by the picture I was making. Something about it was unexpected. The pleasure of making the drawing was there; now the desire to get that reaction came."

It's a reaction that would be familiar to readers of McNeil's science-fiction odyssey FINDER: that feeling of being confronted with something completely surprising and unexpected.

FINDER is mainly seen through the eyes of perpetual outsider Jaeger Ayers, a mixed-race tracker, scout, loner and a ritual scapegoat from a native society living in, and outside, a culture of domed cities set within wildernesses. It's miles away from the 'huge spaceships and enormous guns' stereotypes of SF, with intensely human protagonists and their lives within - and outside - societies that are utterly strange and yet follow completely logical rules.

It incorporates aspects of speculative science fiction with family drama; the high technology of cranial jack computer interfaces with houses set within living trees; the political games played within and between extended clan families. McNeil describes the series as aboriginal SF. "It has to do with 'primitive' cultures meeting 'advanced' ones," she explains. "Scalps and scalpels, trackers and trackballs, ritual magic and videogames."

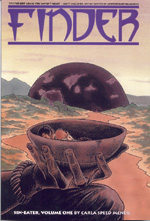

Three volumes of FINDER are now available. The first two cover the 'Sin-Eater' storyline, concerning Jaeger's relationship with Emma Grosvenor, her three children, and her husband Brigham, Jaeger's former drill sergeant and mentor. It reveals some of Jaeger's abilities and character - "He's a strange bastard who keeps turning up on the back steps, a stray cat. Stray cats can do some amazing things, so watch 'em closely". (Check out Ninth Art's review of FINDER: SIN-EATER here.

Three volumes of FINDER are now available. The first two cover the 'Sin-Eater' storyline, concerning Jaeger's relationship with Emma Grosvenor, her three children, and her husband Brigham, Jaeger's former drill sergeant and mentor. It reveals some of Jaeger's abilities and character - "He's a strange bastard who keeps turning up on the back steps, a stray cat. Stray cats can do some amazing things, so watch 'em closely". (Check out Ninth Art's review of FINDER: SIN-EATER here.

The third book, KING OF THE CATS, sees Jaeger in another city, the Disneyworld-like Munkytown, where he insinuates himself into the affairs of a matriarchal society of humanoid lions and into a tribe of his own people. The third major story arc, 'Talisman', is scheduled to appear in trade paperback form in May.

The fusion of elements in FINDER reflects the way that McNeil brings influences and inspiration together. Comics were part of her world from an early age, but it wasn't the usual four-colour heroics that caught her eye. "I simply wasn't interested in heroes or heroics. I did have a brief thing for Wolverine, and thereby discovered that one of my great callings was to bring more hairy guys to comics, but the costumes were just ridiculous." What caught her eye were old horror comics. "The weird, dreamlike quality of the horrors got to me in ways that the flashy fight-scene stuff couldn't."

One image in particular sticks in her mind: "It was very odd, but not very creepy: kids in a huge dim room, like a manor house or a museum, looking through a huge open archway into another, more brightly-lit room. On the far wall, framed, is a tooth - a long, pointed thing; a relic. Ordinary room furniture and other trappings surround. But filling up the enormous room is a ghostly image of a harpooner and the whale from which the tooth came. The idea that deliriously large stories contained in tiny things were reeling around in every spare corner was immensely satisfying to me."

This love of 'gratuitous weirdness' feeds directly into FINDER, but also brings something else: "My highest literary aspiration is to present that strange world, and the limitlessness implied by its unfamiliarity, and still have the stories sharpen into crystalline clarity by their climaxes."

It was at university that McNeil gravitated towards comics as a career - something that the courses on offer couldn't really prepare her for. "Didn't want to make movies, because I love to draw," she says. "Didn't want to paint, wasn't satisfied by single images - I slowly came to understand that a single image is not a story. The more literature classes I took, the more I knew that a single image, even a large group of related images, was simply not enough."

'I do everything by hand - inking, colouring, lettering, all the old-fashioned way.' The path led to telling stories with images, then - a rather narrow field. "Didn't want to be a teeny cog in a Byzantine society, so that let out animation. Couldn't give up drawing, so that let out prose writing. I toyed with commercial art and scientific illustration, but those are also just single images. Strip comics don't work for the kind of story I wanted to tell. There really was no question of what I should do, once I got past animation."

So, with little experience of, and no training in, creative writing, McNeil embarked on a career in spinning stories. Dissecting novels for story structure was a help, but like many science-fiction writers, she takes her inspiration from primary sources. The sociological aspect of her stories is fed by a life-long love of National Geographic - "my bible", McNeil says - and most of the details also come from non-fiction.

"It's funny how far away from the science fiction section of the bookstore I've gotten," she muses. "I gravitate to archaeology, anthropology, zoology, history; almost anything else. I can flip through Carl Sagan, Jared Diamond or Stephen Jay Gould and get a hundred ideas so fast I have to snap them shut before my brain explodes."

Despite the fascination with sciences in all their forms, and a self-confessed love of science writers, McNeil herself is determinedly low-tech. "I'm an utter technophobe, married to a wirehead," she says. "I do everything by hand - inking, colouring, lettering, all the old-fashioned way. I had a fancy graphics tablet that could do damn near everything but darn socks, and I couldn't get used to it."

So it's an organic evolution for each story arc. McNeil jots down story ideas in a binder, and works out plots for each idea. "I'll get the whole outline done, with suggestions for chapter-breaks, and start on the first issue. I'd love to have a full script for each issue, and lately I'm getting better at that, but that's only so I can refine what's already there."

Each page then gets broken down into panels and tiers, and then it's time for the artwork to begin. Rough drawings and layouts are done on the same paper as the script, and are then transferred onto plain white two-ply Bristol board in pencils.

The look of FINDER is as organic as its production, with flowing lines reminiscent of cartooning. "I love cartoony-exaggerated art, like the caricaturist Hirschfeld," McNeil says. "Cartoony art is an odd breed of abstraction that can connect the reader very keenly with facial expression and gesture.

The look of FINDER is as organic as its production, with flowing lines reminiscent of cartooning. "I love cartoony-exaggerated art, like the caricaturist Hirschfeld," McNeil says. "Cartoony art is an odd breed of abstraction that can connect the reader very keenly with facial expression and gesture.

"When you watch a person, or listen to them speak, you're not noticing every detail of their clothing or the chair they're sitting on. You're paying attention only to certain details of their face and voice which tells you what you need to know. You're making a reduced, abstract image of that person in your mind, the better to focus on them. Cartoony art replicates and recreates that process."

As for the characters and situations themselves, McNeil says that they came about through "constant daydreaming". The world of FINDER has been locked in her head since childhood. "It's a little misleading to say that this world has been in my head since I was four," she says. "I have been using it to keep myself amused for that long, but the world itself, and the people in it, have changed radically - not least in response to being written down and drawn about."

Like many authors, McNeil sees her characters almost as independent entities. "A character is a voice," she says. "Everybody's got a bunch of voices in their heads. Untangling them so you can hear them clearly helps the writer make them into characters that can say and do things that are relevant. Those internal voices aren't going away, they're part of you, but they came from other people. Mistaking them for your own voice is dangerous - if you know who they are, you can tell them to shut the fuck up on occasion."

However, McNeil is careful to keep her characters developing, and tries not to reveal too much of them. "A character has to progress to a kind of crystallised form. That makes them into a 'face card'; the reader knows who he or she is and thinks of their story when he or she reappears."

McNeil has completed this with one character, Marcie, the youngest child from the 'Sin-Eater' storyline, in 'Talisman'. "That story played out pretty much exactly as I wanted - the first time that's happened for me - but now she's pretty much told. Marcie is now like a face card, but I can't play her except at the right place, when 'Talisman' can bring some bearing onto what's going on."

'A character is a voice. Everybody's got a bunch of voices in their heads.' It's a process McNeil has had to be careful with in terms of her main character, Jaeger Ayers. "I had nighmares doing issue #22, 'Fight Scene'. It's the first time I laid out, in ways I can't go back on, the details of Jaeger's early life. Only in skips and hops, with lots of unanswered questions, but there are now solid handholds in his past. He's such a complex character to me, it gave me the spins to think of 'using him up' too soon. I have to pay him out slowly and carefully."

Jaeger has, however, made a guest appearance in MYSTERY DATE, McNeil's side project from FINDER. Although set in the same world, MYSTERY DATE deals with different concerns. Only comprising one story so far, it centres around Vary, a student and part-time prostitute (an honourable and accepted profession in this world) and her two sociology professors, one human and one an intelligent feathered reptile.

"I came up with this very cute little prostitute-in-training, an oil-and-water mix of naivete and experience, and she clicked with the two doctors so well, it just took off. Vary was really only supposed to be a throwaway characters. Never underestimate the power of cheesecake."

MYSTERY DATE was originally intended as stories for an anthology, but the experience of producing the first two stories was a mixed one. "I took two of the short stories I'd already down and revised and expanded on them, making two 32-page issues. I did those and a trade paperback, making about a six-month hiatus between FINDER 14 and 15. Well, it wasn't supposed to be a hiatus, but lots of FINDER readers missed them, and thought I'd sunk without a ripple, as do so many small-pressers. So there will be more MYSTERY DATE, but it'll be under my regular banner - 'FINDER: MYSTERY DATE'."

The two professors will also cross over back into the main FINDER storyline. "They were always supposed to be FINDER characters. When their time rolls around, they'll be able to explain quite a lot about the big picture."

So there is an overarching storyline to FINDER? "There are quite a few pieces that affect the whole weave, and so they suggest Big Stories," McNeil says. "But there are a lot of other pieces that need to be in place, and not all of them are there yet. I don't know how long FINDER will be - I hope the world will end up big enough for me to keep setting stories in it for a number of years. It may run out at 75 issues, or it may still be going strong twenty years from now. If it runs out, I'll do something else."

What that something else might be, McNeil isn't sure. She has done projects away from FINDER; notably drawing the relatively unknown story of actress Hedy Lamarr's flair for science and her invention of communications technology for Jim Ottaviani's DIGNIFYING SCIENCE anthology (published by GT Labs). "That was fun; it's the first thing I've done that my parents could actually enjoy. They're happy I'm doing all right of course, but the work itself doesn't make much sense to them."

The conventional comics artist career path - illustrating other writers' scripts - has never appealed to McNeil, but the Hedy Lamarr story is one of a few to benefit from her pencils. She has drawn a couple of issues of SHANDA THE PANDA for Mike Curtis, working "within a sort of manga-meets-Dan-DeCarlo art style".

The conventional comics artist career path - illustrating other writers' scripts - has never appealed to McNeil, but the Hedy Lamarr story is one of a few to benefit from her pencils. She has drawn a couple of issues of SHANDA THE PANDA for Mike Curtis, working "within a sort of manga-meets-Dan-DeCarlo art style".

She also drew a double-page piece for one of TRANSMETROPOLITAN collections, FILTH OF THE CITY. "I was pleasantly surprised how much fun it was to draw Spider Jerusalem. I can't think of any other Marvel or DC characters I'm desperately craving to draw, but one never knows." However, McNeil is happy to "go on record for creator-owned" work.

McNeil is one of the best-known self-publishers, and believes that was her best - and indeed only - route into comics. "If I'd gone hunting work from the majors, I wouldn't have gotten any support from my family, just a lot of stern lecture about How You'll Never Get Anywhere Working For The Man," she comments. There have been many other advantages, though. "I have no axe hanging over me that I didn't put there myself."

McNeil believes that independent creators like her are vitally important to the creative field. "The more entertainment industries try to put all their money on the one mega-blockbuster that will pay all their salaries, the fewer writers and creative people will have any opportunity at all, and the fewer books, movies and albums we'll have. There has to be the garage band and the evening writer. No oaks without soil, no soil without grass. Oaks kill the grass, the grass moves elsewhere."

McNeil, though, has no interest in moving elsewhere for the moment. She's currently finishing the fourth major story arc of FINDER, "Dream Sequence", concerning Magri White, whose exquisitely detailed inner world, which can be visited by people plugging into virtual reality systems, has been invaded by a murderous ghoul. And after that?

"The Big Stories are still very incomplete. I'm not ready for them yet. They're the big waves off the Barrier Reef. Right now I've got four or five stories jotted down that are good possibilities for the issues following "Dream Sequence". There are eight or more ideas that aren't quite stories - they're situations without plots." Clearly, like Magri White, Carla Speed McNeil's fantasy world is going to be providing entertainment and wonder for some years to come.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.