Writer/Artist: Andi Watson

Writer/Artist: Andi Watson

Collecting SLOW NEWS DAY #1-6

Price: $16.95

Publisher: Slave Labor Graphics

ISBN: 0-943151-59-7

It's insanely difficult as of late to find truly good romantic comedy in mediums like film and television. In comics, it's even harder, given that there the genre is virtually nonexistent.

With the exception of rare efforts like Terry Moore's STRANGERS IN PARADISE and '80s indy fave OMAHA THE CAT DANCER, there have been very few romantic comedies in comics.

This is a shame, because romantic comedy is a genre with considerable scope and variety. It can be used as a form of social commentary, a vehicle for over-the-top pratfalls and rapid-fire dialogue, or as a simple tale of two people finding one another.

Andi Watson's SLOW NEWS DAY avoids the pratfalls and the rapid-fire dialogue, but keeps many of the qualities of good romantic comedy; it's like a decaffeinated version of Howard Hawks' HIS GIRL FRIDAY.

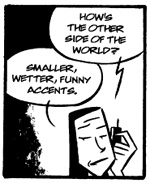

SLOW NEWS DAY concerns the culture clash that ensues when young reporter Katharine Washington (American, natch) takes an internship at the Wheatstone Mercury, a tiny newspaper in a tiny English village so uneventful that the exploits of a school soccer team are front-page material.

She finds herself assigned to assist Owen Holmes, the Mercury's star (read: only) reporter, who is less than pleased at the company. For one thing, she doesn't seem to take the job as seriously as he does; for another, she might be better at it than him.

Time marches on. Katharine and Owen report on a variety of stories, and struggle to get their material noticed in a paper that relies on stories about its major advertisers for income. Owen struggles to commit to his relationship with Nicole (his girlfriend, Katharine's roommate, and a fellow employee). Katharine has her own relationship struggles with a boyfriend back in the States, and with her mother, a respected reporter in her own right, with her own reasons for wanting Katharine at the Mercury. And whatever bond the two reporters might be forming is threatened by Katharine's real motives for joining the Mercury, which are hardly sinister, but cut to the heart of the conflict between her and Owen.

Time marches on. Katharine and Owen report on a variety of stories, and struggle to get their material noticed in a paper that relies on stories about its major advertisers for income. Owen struggles to commit to his relationship with Nicole (his girlfriend, Katharine's roommate, and a fellow employee). Katharine has her own relationship struggles with a boyfriend back in the States, and with her mother, a respected reporter in her own right, with her own reasons for wanting Katharine at the Mercury. And whatever bond the two reporters might be forming is threatened by Katharine's real motives for joining the Mercury, which are hardly sinister, but cut to the heart of the conflict between her and Owen.

In a film of this material, the storyline would be rushed through in an hour and a half of misunderstandings and rapid-fire montages set to current pop standards. Not so with SLOW NEWS DAY; the problem the characters face isn't that they don't understand one another, it's that they don't understand themselves. Owen may pontificate about the importance of his job, but in many ways he uses those beliefs as an excuse to avoid improving his own life. Katharine may underestimate the Mercury, but she does have some insights into how the paper can improve. Even supporting characters like Katharine's mother are made multi-dimensional - she wants her daughter to live up to her potential, but fails to realize that Katharine has to make her own decisions.

None of this characterisation is presented in broad, melodramatic strokes; almost all of SLOW NEWS DAY is presented in a series of tiny vignettes, some lasting less than a page. At first glance, there appears to be a lot of dialogue in the book, due to the large number of panels per page (more on that later).

However, the dialogue is sparser than it might initially appear. Characters speak in short, terse sentences, interrupt one another and make no long speeches, and in fact, they rarely say what they actually mean. In many scenes, a character's true state of mind is revealed through a simple pause, gesture, or facial expression that tells us more about them than even the other characters know.

Observe, for instance, a scene with Nicole, left alone in her apartment while Owen's off on a story with Katharine. We first see an exterior shot of her house at night, followed by a shot of Nicole sitting on the couch watching TV as a door slams off-panel. We next see the lower half of Katharine as she walks in and says "G'night," followed by a close-up of Nicole's scowling face. In four panels, Watson has told the reader all he needs to know about Nicole's feelings for Katharine - and the entire sequence has taken only half a page.

Observe, for instance, a scene with Nicole, left alone in her apartment while Owen's off on a story with Katharine. We first see an exterior shot of her house at night, followed by a shot of Nicole sitting on the couch watching TV as a door slams off-panel. We next see the lower half of Katharine as she walks in and says "G'night," followed by a close-up of Nicole's scowling face. In four panels, Watson has told the reader all he needs to know about Nicole's feelings for Katharine - and the entire sequence has taken only half a page.

Throughout SLOW NEWS DAY, Watson compresses the sequence of events in the story, while decompressing each individual event itself. The average comic page has about three "tiers," or vertical rows of panels that read horizontally. For instance, a six-panel page would have three tiers of two panels each. Here, however, Watson expands the format of each page to four tiers each. This allows an average page to contain about 8-9 panels each, as opposed to the usual 4-6.

This style actually works in favour of the story. Since much of the action consists of people talking to one another, the format allows Watson rapid transitions from one scene to another, while allowing each individual scene to unfold at a realistic pace. There are very few "big" events in SLOW NEWS DAY; rather, there are dozens of small events that establish who these people are and what they need in their lives.

This isn't an easy narrative trick to pull off, but it works thanks to Watson's artwork. His angular characters and sparse backgrounds may appear simplistic at first, but they aptly capture the subtleties of the characters' feelings and the laid-back atmosphere of Wheatstone. For all the panels on each page, the narrative never comes off as cluttered or confusing; the major details of each panel are immediately recognisable to the reader. Visually, the story is told in a straightforward manner. Emotionally, things aren't nearly as simple.

Romantic comedy is a rarity in comics, and when it does occur, it doesn't have to be all one-liners and embarrassing public declarations of love. SLOW NEWS DAY is simply the story of two intelligent, driven people who grow closer over a period of time, and learn something about themselves in the process. As a film, it would be too slow; as a book, it would seem too oriented on the characters' inner thoughts. As a comic, however, it is more than successful at what it sets out to achieve; it's the sequential equivalent of hard candy.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.