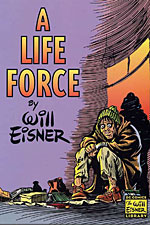

Writer/Artist: Will Eisner

Price: $12.95

Publisher: DC Comics

ISBN: 156389789X

Writer/Artist: Will Eisner

Price: $12.95

Publisher: DC Comics

ISBN: 156389789X

Beginning with A CONTRACT WITH GOD in 1978, Will Eisner entered the final and most fruitful period of his long and many-faceted career.

A few years earlier, at a time in his life when most are beginning to entertain thoughts of retirement, Eisner left his successful commercial enterprise and re-entered the field of comics just as the evolution from comic book to graphic novel was about to take place. Alongside other contemporaries like Jim Steranko, Richard Corben, and Gil Kane, Eisner saw the potential in this new form early enough that it was still more abstraction than fact. In this regard, Eisner was essentially unbridled by form in his creative process as he ventured into territory not yet well explored by American comics artists.

What set Eisner apart from these other well-deserving aspirants and lends staying power to the likeable myth that holds him responsible for the primary development of the graphic novel in America is that he did not just create one and then step away from the drawing board, waiting for the world to recognise his genius. Instead, he used its debut to mark a new beginning that would find him dedicating himself to the discipline of creating long-form works of comics en masse and then applying it to the production of many such pieces in the years to follow.

In a period so fruitful for a prolific artist, it is inevitable that some chances taken pay off better than others as some narrative opportunities are met more ably than others by Eisner's natural talents as a visual storyteller. Dabbling in everything from science fiction to children's stories, Eisner obviously railed against the idea of being perceived as a one-trick pony. But, careful scrutiny of his output finds Eisner at his strongest when dealing with content that is both morally substantive and familiar to him as a person.

This draws our critical attention, then, to Eisner's body of semi-autobiographical works, and more specifically to the ones that are set in the early years of the Depression in a neighbourhood very much like one he grew up in. Nestled in the bosom of this sequence of graphic novels that make up the biggest chunk of his post-CONTRACT output lies perhaps his most successful marriage of technical virtuosity and storytelling excellence, 1985's A LIFE FORCE.

Judging by the many thematic elements shared by A LIFE FORCE and so many of Eisner's other books, one might think that it would be difficult to pick one of them out over the others as demonstrably superior. Yet, it is precisely because he revisits this material so regularly that we can clearly see contrasts in scope and substance between them. Though his narrative concerns may remain constant from one work to the next, the criteria that shapes how he brings the story to the page and what sort of structure it takes is ever-changing, a testament to the unrelenting spirit of innovation that runs the gamut of his output.

Judging by the many thematic elements shared by A LIFE FORCE and so many of Eisner's other books, one might think that it would be difficult to pick one of them out over the others as demonstrably superior. Yet, it is precisely because he revisits this material so regularly that we can clearly see contrasts in scope and substance between them. Though his narrative concerns may remain constant from one work to the next, the criteria that shapes how he brings the story to the page and what sort of structure it takes is ever-changing, a testament to the unrelenting spirit of innovation that runs the gamut of his output.

An element common to most of Eisner's work is his imaginative approach to story structure. When working in shorter, episodic comics forms, Eisner, not unlike George Herriman, forges a consistent style out of finding as many different ways as he can to tell the same basic kind of story. In longer efforts, Eisner regularly treats the individual chapters as structural units and uses chapter divisions to alter his narrative focus, layout approach, pacing, text-to-visual ratio and a holy host of other more subtle formalist considerations. Under varying conditions, these shifts can be so radical as to create a sense of disharmony between the various sections.

Nowhere can this be seen more plainly than in A CONTRACT WITH GOD, which reads more like a collection of shorter works that share a common time and place than a unified work with a clearly articulated theme towards which all of the individual sections are working. In contrast, each chapter/structural unit of A LIFE FORCE ties directly in with all of the book's central conceits, lyrically delivered in narration at the opening.

"After the crash of the Stock Market in 1929, a Great Depression engulfed Western society like a gray cloud. Suddenly it seemed, to a world which had been in gleeful pursuit of the good life, that living had become survival...[b]ut in the Bronx, on Dropsie Avenue, most tenement dwellers remained holding fast to their beach-head simply because they had only just arrived from other more hostile places. They carried with them the tabernacle of a life force that they hardly understood."

The first line sets the time period in place. The second tells us that the characters are already in a state of flux when the story opens. The third sets the location and the fourth hints at the overarching theme that elevates A LIFE FORCE from historical semi-fiction to humanist celebration. While each chapter has its own narrative agenda, all draw vitality from the unity of purpose that inhabits the book.

All of Eisner's work developed along these thematic lines takes on a not unexpected layer of historical significance from the spectre of Nazi Germany looming over the time-specific, Jewish-American worldview it explores. In contrast to the others, though, which merely imply the coming troubles by their position in history, A LIFE FORCE is one of Eisner's only books to deal directly with the events of the Holocaust.

All of Eisner's work developed along these thematic lines takes on a not unexpected layer of historical significance from the spectre of Nazi Germany looming over the time-specific, Jewish-American worldview it explores. In contrast to the others, though, which merely imply the coming troubles by their position in history, A LIFE FORCE is one of Eisner's only books to deal directly with the events of the Holocaust.

Unlike Spiegelman's MAUS, which imports a first-hand account from the witness to its author, Eisner remains true to his strengths as an eyewitness storyteller, evoking a compelling sense of helplessness that came from being distantly removed from the atrocities themselves. While MAUS may offer a vivid contrast between the European and American Jewish perspective of subsequent generations, Eisner's worldview in A LIFE FORCE is both unique and vital, adding new dimensions to our memory and remembrance of one of the world's darkest hours.

This particular outing also finds Eisner using some very effective tools to give his historical backdrop a quality of depth not found in less ambitious efforts like THE DREAMER. The number of pages and the amount of text that Eisner spends on developing this sense of time and place as characters in their own right is a clear indicator of how important he intuits they are for supplying the story with the gravity that it demands.

To achieve this end, he generously draws from sources beyond his own narrative in the form of salient quotes and recreated newspaper clippings from the period, emphasizing the notion that the characters (and the real people that they represent) are unique products of their time and circumstances and can only be clearly perceived by the reader in that context.

With an artist and storyteller so fine as Will Eisner, there is little reason to gloss over any of his many books in order to arrive at a nuanced and complete appreciation of his work. Indeed, it is no overstatement to say that the very worst of Eisner's work is still going to be markedly superior to most of the comics ever produced. But, in the end, genius is a place that even the very gifted only visit a few times in their career and then, only if they are diligent about finding it.

A LIFE FORCE resonates clearly with these tones of genius and through its well-considered themes, well-established time and location, and unity of focus, stands out as a masterwork in a career filled with little but successes.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.