>> Beyond Borders: Mondo Loco

>> Beyond Borders: Every Picture Tells A Story

More...

Steven Spielberg once said that drama is easy. Snap a puppy's leg in front of the camera and presto! People cry! Drama! Pathos!

Now, comedy? That's the real challenge. It's not only that making someone laugh is, in itself, quite difficult. No, to add to the complications, different people find different things funny. There's the smirking connoisseur of irony, the smug bastard on a diet of abuse-rich sarcasm, the turd and spunk slapstick addict, the population of Germany as a whole... Everybody is his own audience, so you can imagine how hard it is to make comedy that is not only consistently funny, but also caters to every taste.

Albert Monteys does it. The bastard brings the funny, God bless him.

As with so many creators in the 90s Spanish scene, Monteys started his so-called-art in the trenches of fanzine-ism, burning up his lunch money on photocopied pamphlets that he bullied his friends and relatives into buying in order to recover some coins for Cheetos and Coke.

As is always the way with all things Spanish, the scene in those days (and in these days, come to think of it) was a mish-mash of infighting and conflicting approaches that could provoke a headache in the most patient of saints.

At its simplest, the conflict could be characterised as between the arty-farty guys in one corner and the nerd fundamentalists in the other. The nerds published superheroic fanzines, while the Crumb wannabees fumbled around the edges of the Madriz movement - named after the legendary magazine and school of artists who indulged in art for art's sake. Any attempt to mix artistic aspirations with a sense of fun was strictly tutted at. Art was supposed to be deep, not fun. Commercial work were supposed to be instant, paper-thin thrills.

At its simplest, the conflict could be characterised as between the arty-farty guys in one corner and the nerd fundamentalists in the other. The nerds published superheroic fanzines, while the Crumb wannabees fumbled around the edges of the Madriz movement - named after the legendary magazine and school of artists who indulged in art for art's sake. Any attempt to mix artistic aspirations with a sense of fun was strictly tutted at. Art was supposed to be deep, not fun. Commercial work were supposed to be instant, paper-thin thrills.

Some authors, like the mono-monikered Max, did try to marry both sides, delivering bodies of work with artistic credibility that attempted to be easily consumable by the regular public, but such attempts were always approached from a high art sensibility. There was no one working to fill the gap between trashy comix, political funnies and nerdcore fanzines in a way that might draw in readers from across the spectrum. Nor had anyone tried to make a comic that, while being artistically or thematically risqué, also managed to be, well, funny. No one, that is, until La Penya released MONDO LIRONDO on an unsuspecting world.

La Penya (The Posse) was a group of four comic-loving university students - Albert Monteys, Alex Fito, Ismael Ferrer and Jose Miguel Álvarez - who put all their pennies together to put out a comic. There was nothing new about this; fanzines are common practise. But what was different about La Penya, and what helped them on the way to success, was that the project benefited from a unified vision. They all worked on the same pages, plotting, dialoguing and drawing together. They would pass the pages around and shuffling wild ideas and plots between them.

What started as a collection of sketches featuring a variety of characters quickly evolved into a cohesive story where every character and tale overlapped with the next, virtually creating a universe out of nothing.

They took the first twenty odd pages, named it MONDO LIRONDO and send it to rookie publisher Camaleon Ediciones, which obviously saw the potential of the series and released Issue Zero, a laugh fest of nuclear proportions. Instant success followed, and the zero issue quickly sold out. Then the same thing happened with the official first issue. And the second. And the third...

In a move never seen before in the Spanish market, the publishers reprinted the issues. And they quickly sold out again. It was madness. A tiny imprint selling by the thousands a black and white amateur comic, created by four inexperienced students and starring anthropomorphic animals that looked like Carl Barks on crack. Nobody saw that coming.

They took the first twenty odd pages, named it MONDO LIRONDO and send it to rookie publisher Camaleon Ediciones, which obviously saw the potential of the series and released Issue Zero, a laugh fest of nuclear proportions. Instant success followed, and the zero issue quickly sold out. Then the same thing happened with the official first issue. And the second. And the third...

In a move never seen before in the Spanish market, the publishers reprinted the issues. And they quickly sold out again. It was madness. A tiny imprint selling by the thousands a black and white amateur comic, created by four inexperienced students and starring anthropomorphic animals that looked like Carl Barks on crack. Nobody saw that coming.

But what made MONDO LIRONDO such a success? Well, first, its roots can be traced back to the much loved and successful old school writing of Spanish funnymen like Miguel Mihura and Ramon María del Valle Inclan. Theirs was a humour both slapstick and cerebral; acidic and self-mocking.

What La Penya did that no one had done before was take those influences and throw in everything and the kitchen sink. There's Crumb sickness in there, plus Toriyama's juvenile poop-shooting, Tati's absurdism, Vázquez's corrosiveness, Disney's innocence, Bark's dynamism, and even a dash of manga, plus 60s Spanish school comic comedy, superheroic antics, 90s attitude, bad language, teen slang, sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll. And funny animals! With stress on the funny, and in both senses.

The story centres on a murder mystery in the Valley of the Zarzamoras, a place like any other with its psycho moles, biker gang coffee cups, prostitute fleas, robber bats, apocalypse-cultist flies, and a gay couple comprised of a chicken and a lemon. Their stories tangle together surprisingly naturally as the comic jumps from one character to the next, and it's always funny. Hysterical, in fact.

Sadly, the story of how the comic was conceived also explains how it ended. A few awards later, La Penya finished their studies. They tried to continue publishing the comic at each other's houses, but neither the magic nor their minds were in the job any more. Eight issues after issue zero, they wrapped the story up in apocalyptic fashion, and split the posse up.

Sadly, the story of how the comic was conceived also explains how it ended. A few awards later, La Penya finished their studies. They tried to continue publishing the comic at each other's houses, but neither the magic nor their minds were in the job any more. Eight issues after issue zero, they wrapped the story up in apocalyptic fashion, and split the posse up.

Ferrer and Álvarez tried to break in to the burgeoning field of hentai Spani-manga, with abhorrent results; Fito embraced the intelligentsia and has become the true heir to Max's throne of weird but strangely appealing comics. And Monteys was hired as an editor by Penthouse Comix - but he had too much talent to waste there. He won the Best Newcomer prize at Barcelona's Comic Festival for his bizarre CALAVERA LUNAR, an extremely funny homage to superhero comics, then signed with El Jueves, a political satire magazine that sells a quarter of a million copies a week, but that was desperately in need of new blood.

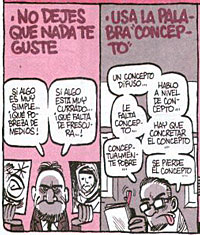

And he's still there, as funny as ever, producing two weekly strips - the hilarious TATO, the diary of a modern young man (so realistic that I'd recommend it to any parent who wants to know what their sons are up to once they leave home), and PARA TI QUE ERES JOVEN ('For You, Youngster') a bright and poignant guide to everyday life that Monteys creates in collaboration with Manel Fontdevila.

Some snobbier critics would disagree, but in my opinion Monteys is not just the best creator of his generation, but the best creator in the Spanish market at the moment. If he were creating more serious work, he'd be every critic's darling. Such is the fate of the comedian.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.