>> The Friday Review: The Birthday Riots

>> The Friday Review: A Distant Soil: The Gathering

More...

Writer/Artist: David Hitchcock

Writer/Artist: David Hitchcock

Price: $2.00 (US), £1.50 (UK)

Publisher: Black Boar Press

It's easier to list the comic industry taboos not broken by WHITECHAPEL FREAK than the ones that are. Every aspect of David Hitchcock's second solo project seems designed to take on the "accepted wisdom" and prove it utterly wrong. From format to script to subject matter, WHITECHAPEL FREAK is a "freak" of sorts itself. A freak, but also a stunningly effective piece of comic storytelling.

The story centres around a freakshow camped on the outskirts of Whitechapel during the Ripper killings. As WHITECHAPEL FREAK opens, the freak show is in both financial and physical trouble. With the Ripper at large, no one moves around during the night, and those that do are vigilante gangs looking for anyone to take their frustrations out on. As a result, the freak show residents are fearful not only for their livelihoods, but their lives.

These are people who already struggle with day-to-day life, and for them to be placed in a situation as emotive as the hunt for the Ripper can only make matters worse. Here is where Hitchcock comes into his own, taking great pains to bring the inhabitants of the freak show to life in as sympathetic and understanding a way as possible.

As a result, there's a constant tension in the freaks' scenes, placing them somewhere between poignancy and horror. There's genuine human emotion here, as we see the relationships the freaks form with one another, and the continuous assaults on their lives and dignity that they suffer.

Indeed, it's how the freaks respond to these hostilities that lies at the heart of the story. Each one reacts differently, some with fear, some with resignation and dignity, and others with savage, emotional violence. The freaks' physical deformities becomes routine, whilw the emotional deformities of the vigilante gangs ultimately makes them far uglier than the freaks could ever be.

This is ground that has been well travelled in the past - after all, X-MEN has always dealt with the persecuted minority and how it reacts to its circumstances. However, where WHITECHAPEL FREAK distinguishes itself is in the unflinching way in which it confronts its characters and their emotions. These are people pushed to the edge of their dignity and restraint, and as they each react in ultimately self-destructive ways, the story takes its most horrifying turns. These are sympathetic people, and the reader is forced to watch them fall apart under the weight the world has placed on them.

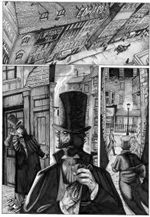

For much of WHITECHAPEL FREAK, the Ripper murders remain in the background. By using them as a canvas for his story, Hitchcock is able to exploit the perceptions and look of the time. His London, picked out in moody greys and blacks, is one of warped, Dickensian buildings, cloaks billowing behind their owners, and palpable danger. This enables Hitchcock to exploit the look of the time for his story. Here, the top hat and cloak wearing gentleman behind you may be a lot more than he looks and your every move could be observed from a rooftop, an alley or a window.

For much of WHITECHAPEL FREAK, the Ripper murders remain in the background. By using them as a canvas for his story, Hitchcock is able to exploit the perceptions and look of the time. His London, picked out in moody greys and blacks, is one of warped, Dickensian buildings, cloaks billowing behind their owners, and palpable danger. This enables Hitchcock to exploit the look of the time for his story. Here, the top hat and cloak wearing gentleman behind you may be a lot more than he looks and your every move could be observed from a rooftop, an alley or a window.

This bleak, oppressive London is superbly evoked by Hitchcock's scratchy, slightly melodramatic style, making WHITECHAPEL FREAK an unusually atmospheric piece. The art creates a very strong sense of place within the story, the London of WHITECHAPEL FREAK becoming as real and sordid as the cities of BLADE RUNNER and SE7EN.

However, the Ripper murders do not remain in the background. As the story nears its end they are brought forcibly to the forefront of events, and once again Hitchcock manages to put an unusual new spin on things. There's a genuine sense of tragedy as the story closes, with the freak show residents being drawn in to the Ripper case and their fates becoming forever connected to his.

Inevitably, WHITECHAPEL FREAK will be judged against Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's FROM HELL, and superficially the two titles are very similar. Both deal with the Jack the Ripper murders, both take great pains to evoke their chosen time period and both end with questions unanswered.

Having said that, the similarities are all cosmetic. Where FROM HELL uses the Ripper murders as the starting point for a much larger story of historical consequence, WHITECHAPEL FREAK weaves the murders into its own tale. Not simpler, but different, WHITECHAPEL FREAK treads the same ground in it's own way and works all the better for it.

WHITECHAPEL FREAK's dedication to the period it deals with is even present in its format. Instead of the usual 22-page pamphlet, WHITECHAPEL FREAK is printed on newsprint and is tabloid-newspaper sized. Three times the size of everything else on the shelf, and picked out in grim looking monochrome, it's impossible to miss when placed next to the much smaller, brightly coloured pamphlets put out by other companies.

To find out more about David Hitchcock, check out Ninth Art's interview. This format also serves another purpose, providing a visual cue to the reader on exactly what they can expect from the comic. Its size, shape, and a cover depicting a lurid demon-faced Ripper, all evoke the penny dreadfuls and newspapers of the time. In short, WHITECHAPEL FREAK begins to tell its story the second a reader looks at it, its format as much a part of the story as is its content. It's a brave move, and one that pays dividends.

Hitchcock's story sets itself near impossible goals and succeeds at every single one. The story neatly side-steps comparisons with FROM HELL, using the Ripper murders to tell a story reminiscent of Hammer Horror at its best. Hitchcock's art portrays London as a dank and seedy city never visible for more than a couple of streets at a time, making it in many ways the exact opposite of FROM HELL. It's a street-level story that stays there, eschewing the more intellectual dimensions of FROM HELL for something more emotive.

Here, the human impact of the murders is the focus, as Hitchcock weaves a tragic story of people caught up in events too big for them to understand or appreciate. Their struggle, and ultimate failure, to make a life for themselves is uncomfortable but compelling reading. Just like viewing a freak show.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.