>> The Friday Review: The Birthday Riots

>> The Friday Review: A Distant Soil: The Gathering

More...

Writer/Artist: Martin Rowson

Writer/Artist: Martin Rowson

Based on the novel by Laurence Sterne

Price: $26.95

Publisher: Overlook Press

ISBN: 0879517689

I was born in the early hours of the morning of 4th October 1976 in a maternity home on the Isle of Man. A few hours after this event, a Royal Navy Submarine, the OSIRIS, left port a quarter mile away. I've always been interested in Egyptology, and THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER is one of my favourite films. According to THE LIFE AND OPINIONS OF TRISTRAM SHANDY, GENTLEMAN, these three facts are connected.

Widely regarded as one of the best English comic novels ever written, TRISTRAM SHANDY is an enigma at almost every level. A fictionalised autobiography, written by clergyman Laurence Sterne, it sees the eponymous Mr Shandy attempt to place his life and personality in some kind of perspective by recanting the events that led up to it.

His theory goes that these events must have had a formative impact on him, and as a result are at least as worthy of inclusion in his autobiography as the details of his own life. As Shandy leads us through his life, he passes comment on people and locations he encounters, and continually tries to understand not only who he is, but why he is.

Unfortunately, he never really manages this. TRISTRAM SHANDY is one of the earliest and best examples of postmodernist fiction, with the central subject of the novel never actually being examined in any detail, and the "path" taken through the text being at least as important as the text itself.

In this case, the path is long and torturous, with both character and reader only ever catch glimpses of Shandy, sandwiched between long stories about his Uncle Toby and the dilemmas of choosing a midwife over a doctor. This deliberately absurd approach works supremely well, and TRISTRAM SHANDY is still regarded not only as a seminal post-modern text, but also as a highly effective comic novel.

Despite the unusual nature of both text and subject matter, TRISTRAM SHANDY lends itself to sequential art remarkably well. After all, textual awareness of this kind is pretty much compulsory in comics these days. Whether it's the latest examination of the "archetypal" comic stories (Alien visitor raised by farmers, human recruited to be galactic policeman, convenience store workers agonising over their lives), or the fourth-wall breaks perfected by the likes of THE INVISIBLES, comics are an insanely self-aware medium. As a result, a novel so neurotically self-aware as TRISTAM SHANDY is well suited to graphic adaptation.

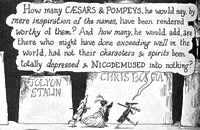

It's with the graphical elements that political cartoonist Martin Rowson is most at home in his adaptation of Sterne's novel. As Tristram's diversions get more and more outlandish, Rowson's art rises to the occasion.

It's with the graphical elements that political cartoonist Martin Rowson is most at home in his adaptation of Sterne's novel. As Tristram's diversions get more and more outlandish, Rowson's art rises to the occasion.

Vomiting whales jostle for position with film crews and the heavens, and all the while, Tristram, blissfully unaware of the mayhem he's causing, leads a tour group of readers through his text. A text that, in Rowson's hands, is in a constant state of flux. Here, the page layouts vary to match the subject matter, with splash pages following everything from the standard six-panel grid to an entire page of binary coding.

It's at points like this that the skill with which Rowson has adapted this near impossible text becomes clear. At first glance, this is a book hobbled not only by its structure but also by the simple passage of time. After all TRISTRAM SHANDY's humour has not aged particularly well, much of it locked away in the intricate language and societal mores of the time.

This gap between reader and text is the greatest weakness of the book, but in Rowson's hands it becomes not only a strength, but one utterly in keeping with the original text. Rowson also appears in the graphic novel, along with Pete, his dog and bodyguard. As the two journey through the text, it becomes clear that Rowson is a rampant SHANDY enthusiast, whilst Pete has no idea what's going on and is getting progressively less happy about that as time goes by.

As the novel progresses, Pete becomes the voice of reason and modernity, constantly searching for meaning where there often isn't any, while Rowson's enthusiasm enables him to place the novel in a historical and literary context. In doing so, of course, he also drives home what a pointless exercise that is, adding another layer of meaning and absurdity to a book already laden down with it.

This absurdity, as opposed to Tristram's life, is what lies at the heart of the novel. Time and again, Sterne uses the structure of his book to illustrate the sort of man Tristram is, while regularly descending into irrelevancy or nonsense. At times like this, it's not the content of the chapter, but it's geographical location within the book, and sometimes even it's typesetting, that's important. This is structural rather than contextual literature, and when viewed in that way, it becomes less a book and more a piece of architecture.

This isn't so much a novel as a structure built around the space where a novel should be, and as a result is a unique reading experience. After all, where else would you find an entire page rendered in black due to the author's grief? Or, in one of Rowson's additions to the text, Oliver Stone directing the film version of TRISTRAM SHANDY?

This isn't so much a novel as a structure built around the space where a novel should be, and as a result is a unique reading experience. After all, where else would you find an entire page rendered in black due to the author's grief? Or, in one of Rowson's additions to the text, Oliver Stone directing the film version of TRISTRAM SHANDY?

Rowson's literary gushing serves not only to further muddy the waters of the text, but to place it in both a historical and literary context. Rowson adds extra dimensions to the text, bringing it up to date and commenting on the novel's effectiveness in the modern world. When the novel is accidentally digitised, Rowson and Pete find themselves wandering through ghastly modern interpretations of the novel, from a Raymond Chandleresque piece of noir to a materialistic Brett Easton Ellis version.

However, there are problems with the book, not the least of which is how little sense it makes. Despite Rowson and Pete's continual attempts to comprehend the text, it's always just out of their reach. Shandy, whose face we never fully see, is always just a few steps ahead of them and almost always heading in an entirely different direction.

To understand TRISTRAM SHANDY, it must be read differently, and if possible from a distance. Then, each diversion, when viewed with the others, actually constructs a portrait of Tristram. He's so focused on trying to find some meaning in his life that he never actually gets around to discussing it. As a result, the diversions that he takes the reader on tell us more about his character than an actual biography ever could.

TRISTRAM SHANDY is both a unique novel and a unique graphic novel. Rowson's scratchy, absurd style is perfectly suited to the task of adapting it, and through the extra dimension of his own quest, Rowson manages to comment on the novel. It's difficult to get through in places, but overall this is a highly effective and strangely affectionate adaptation of one of the most famous and least read pieces of English literature. It's a work that rewards perseverance.

And besides, the sequence with the vomiting whale is fantastic.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.