>> The Friday Review: The Birthday Riots

>> The Friday Review: A Distant Soil: The Gathering

More...

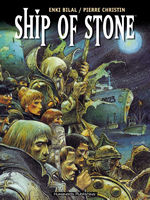

Writer: Pierre Christin

Writer: Pierre Christin

Artist: Enki Bilal

Price: $14.95

Publisher: Humanoids Publishing

ISBN: 1-930652-39-9

Comics and films share a fascination with certain fictional archetypes. The cop on the edge, the hero with a troubled past and the conveniently placed (not to mention usually disposable) scientist who explains the plot, are all mainstays of action movies and a lot of mainstream comics.

The logic behind this is simple: People respond to archetypes or ideas they've already seen. A lot of the time it's not particularly original, but it does the job. SHIP OF STONE follows this route, to a point. Instead of the usual action and horror movie stereotypes, it combines supernatural fantasy with the sort of story normally seen in films such as LOCAL HERO, WAKING NED and WHISKEY GALORE.

A large format hardback published by Humanoids Publishing, the front cover depicts a flock of people clustered around a grim, bearded figure. Drawn in oceanic blacks and greens, the old man has a messianic look to him, but he is not the element of the cover that draws your attention. The people surrounding him do that, due to their absolute normalcy.

These aren't the chiselled, photogenic faces so beloved of most American titles, but rather, a group off weary-looking, plain people of various ages. They look careworn and tired, and it's unclear whether they're surrounding the old man for instruction or for comfort. In short, they look flawed, and it's this imperfection that lies at the heart of the story.

The characters are all inhabitants of Trehoet, a small French village that is in the process of being bought up by a local property developer. The town is a fishing community, the sort of place where everyone knows everyone else. Its only distinguishing feature is the castle on the hillside above it, and the legends surrounding it and the old man who has supposedly lived there for hundreds of years.

The characters are all inhabitants of Trehoet, a small French village that is in the process of being bought up by a local property developer. The town is a fishing community, the sort of place where everyone knows everyone else. Its only distinguishing feature is the castle on the hillside above it, and the legends surrounding it and the old man who has supposedly lived there for hundreds of years.

The problems the villagers face are twofold. The first is that the property developer wants to demolish the village and castle to build a high-end resort. The other is that there's really no good reason for him not to. Trehoet is on poor farming land, far from any major fishing grounds and has a tiny population. The village is barely profitable enough to support the handful that live there, so when the property developer moves in, it's difficult to find reasons to fight him.

To make matters worse, the inhabitants of Trehoet are dreadfully aware of their lot. This is particularly obvious with the protagonist of the piece, a nameless sailor without a home, who settles in Trehoet only as long as he feels comfortable. The sailor has sufficient distance from the village and the situation it finds itself in to accept the incredible events that begin to unfold, and finds a kinship of sorts with the inhabitant of the castle.

His sense of dissatisfaction and unease is found at the heart of several of the characters. The village priest feels uncertain about the town's future, a gendarme providing security for the building project feels he's on the wrong side, and Joseph Gluarec, an ageing collaborator from World War 2, longs for the return of his beloved Reich.

The defining factors in almost all the main characters are unease and discontent, and this only makes the villagers' situation worse. They aren't even sure of themselves, let alone the town they live in. There's an unusual maturity of character here; no revolutionary concepts, but rather, convincing, well-rounded characters that are painfully human. They worry, they snap, and they are prone to the sort of petty rivalry that can boil in towns like Trehoet for decades.

What anchors both them and the town however, is the castle and the history that surrounds it. The castle and its inhabitants become the glue that holds Trehoet together, a kind of visual shorthand not only for the history of the town but for the spirits of everyone who has ever lived there.

What anchors both them and the town however, is the castle and the history that surrounds it. The castle and its inhabitants become the glue that holds Trehoet together, a kind of visual shorthand not only for the history of the town but for the spirits of everyone who has ever lived there.

In short, it represents not only the town but also the very idea of the town. As a result, the book becomes a social commentary of sorts; its central conflict evolving from new vs. old and history vs. change. The villagers are forced to consider that Trehoet may not be profitable, but it's still their town, and it means more than just the land it sits on.

It's a credit to Bilal's writing that he expresses these political and sociological themes through a genre traditionally associated with terms like "feelgood". At no point does SHIP OF STONE become cloying and sentimental. Instead it continually portrays its characters and their situation in a detached, almost minimal style. This serves two purposes, firstly, bringing the characters to the fore, and secondly, giving the more fantastic images tremendous impact.

It sounds facile to describe a story with so many stock elements as unique, but it's true. Bilal uses the visual and spiritual anchor of the castle to construct a story in which the sociological elements stand side by side with physical comedy and supernatural fantasy. It's not perfect, but then, neither are the inhabitants of Trehoet.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.