>> Star of Macedonia: An interview with Ed Piskor

>> Comment: Craig's Last Hunt

More...

The best art speaks to something fundamental in our souls, whether it's love or hate, hope or fear, lust or lamentation. The best art travels well, crossing borders and boundaries of race, creed and religion. The best art speaks to us all.

Enter your friendly neighbourhood Spider-Man.

Seriously. There's a reason why people have been reading Spider-Man comics for forty years. There's a reason why more people saw the 2002 movie - and are going back for more with the sequel - than have ever looked twice at the comics. And it's not because of the marvellous CGI.

Spider-Man - Peter Parker - is a character that people relate to on a number of levels: kids respond to the boisterous adventures, coupled with the character's co-dependent relationship with his foster mother. Older (or smarter) children and young adults also respond to the character's self-deprecating, outsider nature, the relentless stream of problems, and the cheerfully awkward romantic element. And adult readers - or, at least, those who give a little thought to the matter - see Spider-Man for what he is: a celebration of youth and being young; of those few sacred moments when you hit seventeen or eighteen and the world opens up before you with infinite promise and possibility... before closing behind you with a depressingly final thud.

It's no wonder, then, that from Anchorage to Wellington, from Soweto to Southampton, people can't get enough of that friendly neighbourhood action.

This degree of cross-cultural appeal might appear shocking to the uninitiated, of course: while Spider-Man is popular the world over, he remains, fundamentally, a white, lower-middle class American. Conventional wisdom suggests that people like characters they can relate to - that remind them of themselves. So why does this masked Manhattanite travel so damn well?

The clue may be in the question: many observers, including co-creator Stan Lee, have noted that Spider-Man's mask, which covers his face and hides his eyes, allows people to project their own identity onto the character. In theory, looking at the character from within the fictional universe, he could be any man under that mask: black, white, Asian or whatever. And, being any man, Spider-Man therefore becomes Everyman, which explains much of the character's longevity. He's always been known as "The Hero Who Could Be You," after all.

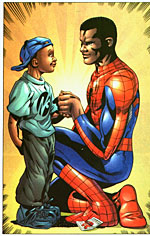

Recent stories have exploited this notion of Projection to poignant effect, such as Paul Jenkins and Mark Buckingham's 'Heroes Don't Cry', in which a black Spider-Man acts as both imaginary friend and father figure to a lonely, neglected child.

Recent stories have exploited this notion of Projection to poignant effect, such as Paul Jenkins and Mark Buckingham's 'Heroes Don't Cry', in which a black Spider-Man acts as both imaginary friend and father figure to a lonely, neglected child.

(It's interesting to note that, in a recent poll conducted by The Sun, Spider-Man came top in a list of Fantasy Dads...although the competition included Homer Simpson, Strider Aragorn and, inexplicably, Joseph Mengele.)

What's doubly interesting is that, despite the best efforts of many a patriotic (if unimaginative) cover artist, Spider-Man isn't as closely tied into a broader American identity as other superheroes, as much as he is linked to New York City. Indeed, the Big Apple is as much of a supporting cast member as Aunt May or J Jonah Jameson.

Spider-Man doesn't fight for Truth, Justice and The American Way. He fights to make his world better, because he has to. Because he can. And because otherwise, he can't face himself in the mirror.

But what happens when Spider-Man is taken out of his friendly neighbourhood?

Recently, the Gotham Entertainment Group, which prints and distributes licensed comics from Marvel, DC, and others to countries all over South Asia, announced that they would be publishing original Spider-Man adventures, written and drawn by Indian creators, and starring a brand-new, Indian-born Spider-Man.

Debuting in July in India (and later appearing in the US), Gotham Comics' Spider-Man will chronicle the adventures of Pavitr Prabhakar, a young boy from Mumbai who receives his spider-powers from a mystical yogi, instead of the trusty arachno-bite. Pavitr will be spinning his web (or "jaal") above the streets of Agra, fighting a demonic Green Goblin for the fate of the world at the Taj Mahal.

Debuting in July in India (and later appearing in the US), Gotham Comics' Spider-Man will chronicle the adventures of Pavitr Prabhakar, a young boy from Mumbai who receives his spider-powers from a mystical yogi, instead of the trusty arachno-bite. Pavitr will be spinning his web (or "jaal") above the streets of Agra, fighting a demonic Green Goblin for the fate of the world at the Taj Mahal.

The new Spider-Man, while staying true to the basic roots of the character, will be reinvented with careful attention to local detail: instead of the stifling one-piece bodysuit, Pavitr Prabhakar will sport a dhoti-kurta costume, complete with webbed loincloth. The mask, shirt and basic colour scheme stay the same, of course: you can't deviate too far from the trademark, after all.

Pavitr's enemies, too, will spring from Indian customs and mythology, giving the new Spider-Man a strong cultural context that good old Peter Parker lacks - or, at least, it'll give him a different sort of context. The best Spider-Man villains - Doctor Octopus, for example - are more of a reflection of Peter Parker than they are of American society, especially since the end of the Cold War.

While this might well be the most comprehensive and ambitious adaptation of the Spider-Man story outside of the big screen, it's not the first time the character has been reinvented for a local audience. Ryoichi Ikegami (CRYING FREEMAN) adapted Spider-Man for Japanese comics in the late seventies, recasting lonely outsider Peter Parker as lonely outsider Yu Komori. The basic set-up remained unchanged from the original comics: Yu Komori was a student who received his powers after being bitten by a spider. He donned familiar tights, worked for a suspiciously familiar and irascible boss, and fought villains such as The Lizard, Electro and Mysterio. He even had a girl to angst over, just like Peter Parker.

Ikegami's Spider-Man, while recalling in both atmosphere and figurework the original Steve Ditko comics, nevertheless felt much bleaker than the American version. At the time I first read the reprint series, during the late-nineties, this made a refreshing change from the bland fare on offer in the other eighty-three monthly Spider-comics. And it was certainly far better than the abominable Marvel Mangaverse series. Unfortunately, the run only lasted for 31 issues, and the reprints suffered from being both poorly translated and hideously expensive. Dreams of remastered, rewritten trade paperbacks of Ikegami's Spider-Man remain just dreams.

Ikegami's Spider-Man, while recalling in both atmosphere and figurework the original Steve Ditko comics, nevertheless felt much bleaker than the American version. At the time I first read the reprint series, during the late-nineties, this made a refreshing change from the bland fare on offer in the other eighty-three monthly Spider-comics. And it was certainly far better than the abominable Marvel Mangaverse series. Unfortunately, the run only lasted for 31 issues, and the reprints suffered from being both poorly translated and hideously expensive. Dreams of remastered, rewritten trade paperbacks of Ikegami's Spider-Man remain just dreams.

Given the notion that people enjoy characters that speak directly to their specific situation and experience, it's hard to see the friendly neighbourhood franchise as a particularly bad thing. No matter what it says on his driving license, he's still Spider-Man, right?

And while some purists might argue that, if Peter Parker is so universal a character, he doesn't need reimagining or relocating, I say: to hell with it. If this is a way to inject new blood and bring a new readership to Ol' Web Head, then I'm all for it. Peter Parker turns 42 this month: he's going nowhere.

And beyond Pavitr Prabhakar, what next? The return of Yu Komori? Can we expect to see The God of Spidermen, spinning two webs at once, John Woo-style, across Deep Water Bay? Is there an African Arachno-sapient on the horizon, combining the adolescent drama of Peter Parker with the trickster comedy of Anansi the Spider Man?

My only fear in this case is that local creators might get swallowed up in the Great Marvel Machine. And as much as I love reading new Spider-Man adventures every month, I'd just as soon see these artists creating their own characters, with their own local flavours, as I would see them reinvent The Hulk as a mopey Samoan.

It makes Spider-Sense to me, anyway.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.