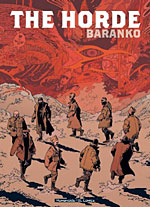

>> The Book Review: The Horde

>> What About Bob? An interview with Bob Schreck, Part Two

More...

Writer/Artist: Baranko

Writer/Artist: Baranko

Colourists: Dave Stewart and Charlie Kirchoff

Translation: Pat McGreal with Baranko

Publisher: Humanoids

ISBN: 1-4012-0360-4

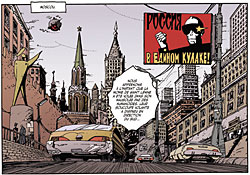

In 2040, Russia is ruled by an insane, drug-addicted former-science fiction writer. The Third Chechen War ended a decade ago, when Russia used its nuclear arsenal, and the sentry posts on the border haven't seen a living soul emerge from the wasteland since. Globalisation failed in 2024. Flying saucers are running rampant, kidnapping people and even the mummified body of Lenin from his Red Square mausoleum. A woman meditates in an abandoned apartment building in the flooded city of Kyzyl, seeking enlightenment.

And life would be just fine if the President hadn't just asked the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church to canonise Genghis Khan.

While tripping on drugs, the current Russian dictator has a vision realising that he is the reincarnation of Genghis Khan. Further, he realises that every thousand years there is an invasion from East Asia that conquers largely the same territory, halting in Eastern Europe - the Scythians in the 3rd century BCE, The Huns in the 7th century, and the Mongols in the 13th. His vision of the future of Russia is tied to this realisation. "It is time to show that Russia is not the descendant of tiny Slavic States in Eastern Europe, but of the Golden Horde, which united East and West!"

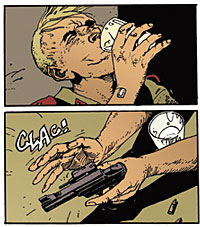

Pan-Slavism on drugs, perhaps, but it sets into motion the secret service's search for the body of Khan's previous incarnation, a lama who was killed in the religious purges of the 1930s and buried in the Ukraine. Meanwhile, a man walks out of the Chechen wasteland, who fears nothing and seeks nothing, but knows that if he fulfils his task, Allah will send him to heavenly Chechnya.

The story is being told to us and commented on by the lama's great-granddaughter, the young woman meditating naked in an abandoned apartment building of a ruined city. Baranko isn't using her as a framing device or trying to create a metatext, he's doing something more complex than that. The closest story I can compare it to in comics is in Grant Morrison's THE INVISIBLES where Ragged Robin is the storyteller and a participant in the story - a story also heavily influenced by Buddhist thought.

The story is being told to us and commented on by the lama's great-granddaughter, the young woman meditating naked in an abandoned apartment building of a ruined city. Baranko isn't using her as a framing device or trying to create a metatext, he's doing something more complex than that. The closest story I can compare it to in comics is in Grant Morrison's THE INVISIBLES where Ragged Robin is the storyteller and a participant in the story - a story also heavily influenced by Buddhist thought.

Here she is seeking enlightenment, but finds herself drawn into the story as it unfolds, and becomes a key player in it as she seeks the sulde of Genghis Khan, or his thirst for conquest. Killed at the height of his power, Khan's sulde took on a spirit of its own as his soul reincarnated over the centuries.

Baranko, like the characters in his book, is trying to link Russia, Ukraine and the other Soviet republics with Asia, something rarely thought about in West. Part of this is due to the nature of the Cold War and the way the world map has been viewed for the past century, with Europe caught between the US and the USSR. But it can also be tied to the fact that, although Russia has always been part of both continents and many cultures, its governments (and by extension its political systems, religions and culture) have of late been affected far more by Western influences than Eastern ones.

THE HORDE will come as quite a shock to those who are familiar with Baranko as the writer-artist of two comic adventure series from Slave Labor Graphics, PIFITOS and SKAGGY THE LOST. They were interesting projects, well written and beautifully designed. The stories seemed to be trying to stretch their way into multiple directions at once, encompassing comedy and tragedy, adventure and romance to create a wild madcap amalgam similar to the old epics he was parodying and drawing inspiration from. They didn't have nearly the impact they should have, which may say more about the industry than the books.

THE HORDE will come as quite a shock to those who are familiar with Baranko as the writer-artist of two comic adventure series from Slave Labor Graphics, PIFITOS and SKAGGY THE LOST. They were interesting projects, well written and beautifully designed. The stories seemed to be trying to stretch their way into multiple directions at once, encompassing comedy and tragedy, adventure and romance to create a wild madcap amalgam similar to the old epics he was parodying and drawing inspiration from. They didn't have nearly the impact they should have, which may say more about the industry than the books.

Ultimately they had the feeling of minor works, and reading THE HORDE, it is a rare experience of seeing an artist come into his talent - and in Baranko's case, his talent is considerable. The canvas is larger, and he struggles to find a way to convey it even as his true concerns lies in the spiritual journeys that underlay the story. It feels like a project that has been percolating for years, but it emerges from his pen fresh and dynamic, with an energy that suggests he was still writing it as he went along.

At the end of the book, a question is posed; "What was this story all about?" The intention isn't to provide an answer, or even to drag one from the reader, but for the reader to use it as a koan to meditate upon: To think about the cultures that bind us together, the lines between nations, the relationships between our lives and our potential; what do the flying saucers have to do with anything?

The greatest compliment I can offer THE HORDE is that after reading the book multiple times, I'm left wanting more. Not unfulfilled, as if the book has failed to live up to its own expectations, and not even as if the story hasn't been finished; just that for all the insanity and chaos and madness, I want to spend more time in this world. Its mixture of the fantastic and the impossible and the all too real leaves me wondering, what was it all about? I don't get that from too many books.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.