>> The Friday Review: Zero Girl

>> The Friday Review: Ruse: Enter The Detective

More...

Writer/Artist: Sam Kieth

Writer/Artist: Sam Kieth

Colourists: Alex Sinclair, Nick Bell

Letterer: Nagmeh Zand

Additional Inks: Jim Sinclair

Collecting ZERO GIRL #1-5

Price: $14.95

Publisher: DC Wildstorm/Homage

ISBN: 1-56389-8519

If, as we rightly insist on this here very site, comics are to be taken as a legitimate literary form, then, as has also been said here often, comics need to be acknowledged as a diverse literary format, and not one tied to any particular genre or style.

And, of course, in looking across the spectrum of comics available we do see comics running the same gamut that prose-only literature runs - with comics embracing genres and styles across the entire spectrum - from realism to absurdism. It's towards this latter end of the scale that Sam Kieth's acclaimed ZERO GIRL falls.

ZERO GIRL tells the story of Amy Smootster, a bespectacled, gawky, vaguely punky high schooler, as she contends with abusive bully girls, reincarnated insect philosophers, an attractive young guidance counselor and both evil and good geometric shapes.

I say "story," but I use the term only loosely; as postmodernist literature, ZERO GIRL isn't as concerned with story, or, for that matter, character, theme or, especially, any kind of moral message, as it is with its own style. ZERO GIRL is about ideas, and the characters and loose plot they inhabit, while not without import, can come across as no more than a framework to hang those ideas off of.

What makes a postmodern comic book like ZERO GIRL so ripe with possibility, though, is that it's a comic book - that is, a work of graphic art just as much as a piece of literature. When we look at writers who famously broke with literary tradition and shattered boundaries - writers like James Joyce - we find they are still limited to words. While what these writers have historically done with those words may be brilliant, and while there may be something to be said for the advantages of the images a reader creates in his mind as opposed to literal images, in an aesthetic sense these writers are limited.

What makes a postmodern comic book like ZERO GIRL so ripe with possibility, though, is that it's a comic book - that is, a work of graphic art just as much as a piece of literature. When we look at writers who famously broke with literary tradition and shattered boundaries - writers like James Joyce - we find they are still limited to words. While what these writers have historically done with those words may be brilliant, and while there may be something to be said for the advantages of the images a reader creates in his mind as opposed to literal images, in an aesthetic sense these writers are limited.

Kieth, as both writer and artist, gets to play with his twistings of reality, with his surrealist notions, by making use of both language and images. So, for example, when Amy introduces the idea that squares are evil and circles are good, Kieth also gets to show us those demonic squares and angelic circles. Indeed, the notion fairly cries out for the graphic arts. Kieth's art is able to accomplish something that mere words never could.

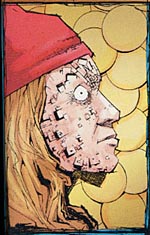

What makes Kieth so effective an artist is that his sensibilities as a both an illustrator and writer are so well matched. The stories he tells are disjointed and loose, they pop and start rather than flow smoothly, and his art is similar aesthetically; its panels jam up against each other, sprawling diagonally across a page or simply getting shoved upright to lie vertically at a pages' edge.

Finished pencils give way to what look like watercolors, or rough pencil sketches, and some panels are torn and slashed by the story. Margins get doodled in or covered with graffiti, or simply don't exist. The story's looseness and surreal qualities are mirrored in the art; it's this melding of the writing and art that is so unique to comics, and that makes ZERO GIRL so effective.

As for the story itself, well, as I said, it is, in some senses, secondary. That's not to say that ZERO GIRL is plotless, or without any kind of a narrative structure. There is a story here, and, for all of the surrealist, Dadaist notions he plays with, Kieth is exploring a specific emotional conflict - the somewhat tender one of relationships between teenagers and adults - through real characters, not archetypes or symbols.

As for the story itself, well, as I said, it is, in some senses, secondary. That's not to say that ZERO GIRL is plotless, or without any kind of a narrative structure. There is a story here, and, for all of the surrealist, Dadaist notions he plays with, Kieth is exploring a specific emotional conflict - the somewhat tender one of relationships between teenagers and adults - through real characters, not archetypes or symbols.

The core of the book is the relationship between Amy and her guidance counselor, Tim. At the beginning of the book, Amy comes to Tim for help; she is homeless, she's being threatened by other girls, and she has the dual problems of threatening squares and feet that emit a strange liquid when she's embarrassed. Tim takes an interest and tries to help her, even going so far as to allow her to crash in his office.

As the book progresses, we see what starts out as innocent flirtation on Amy's part - really her delight at making the adult squirm by teasingly forcing him to acknowledge her sexuality - becomes something deeper. Before long, Amy falls in love with the older man, and it is Tim's reaction to her increasingly more direct advances, and the relationship's eventual resolution, that are at the heart of the story.

While the story is secondary to Kieth's style and literary mode, it would be misleading to suggest that it's not important. ZERO GIRL's use of surrealism and postmodernism seems to be the books' real reason for being, yes, but the story these modes are telling shouldn't be overlooked. What we have here is an odd melding of what ends up being a fairly emotionally involving story with the distancing stylistic choices Kieth employs in his art and book. These two poles invariably cause some tension, and there are moments where the book seems unsure of itself, where the surrealism is overpowering the heart of these characters, or vice versa. To Kieth's credit, these moments are few and far between.

ZERO GIRL can come as something of a shock to those accustomed to more traditional narrative styles, but, even for those unprepared souls, it has much to offer. The trade, in addition to collecting the five issues of the story and covers, includes a highly illuminating afterword by Kieth, and an introduction by none other than Alan Moore.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.